01 Jan 1999

title: “Precision Inquiry for the Desired Future State”

Precision inquiry is the practice of establishing the most sensory-complete set of information the client can give you about what their Desired State will be. These questions can be asked from the present or the future; often times asking from the future is more productive especially if the client does not really consciously know what they want.

I wrote this initially back in 1999–2000 to try to capture the process we used in our internal consultancy at Hewlett-Packard, the Software Initiative.

Desired State

The goal of Precision Inquiry, the Desired State, is a description of the client’s desired future, how they would like things to be.

It is typically derived by gathering Well Formed Outcomes for the future. One’s future desired state is very powerful for people to have; it provides a target for them to move towards, gives purpose for change and helps them determine what they need to know, acquire and do in order to get that desired future. The Three Golden Questions are often used to create a rich desired state for the client.

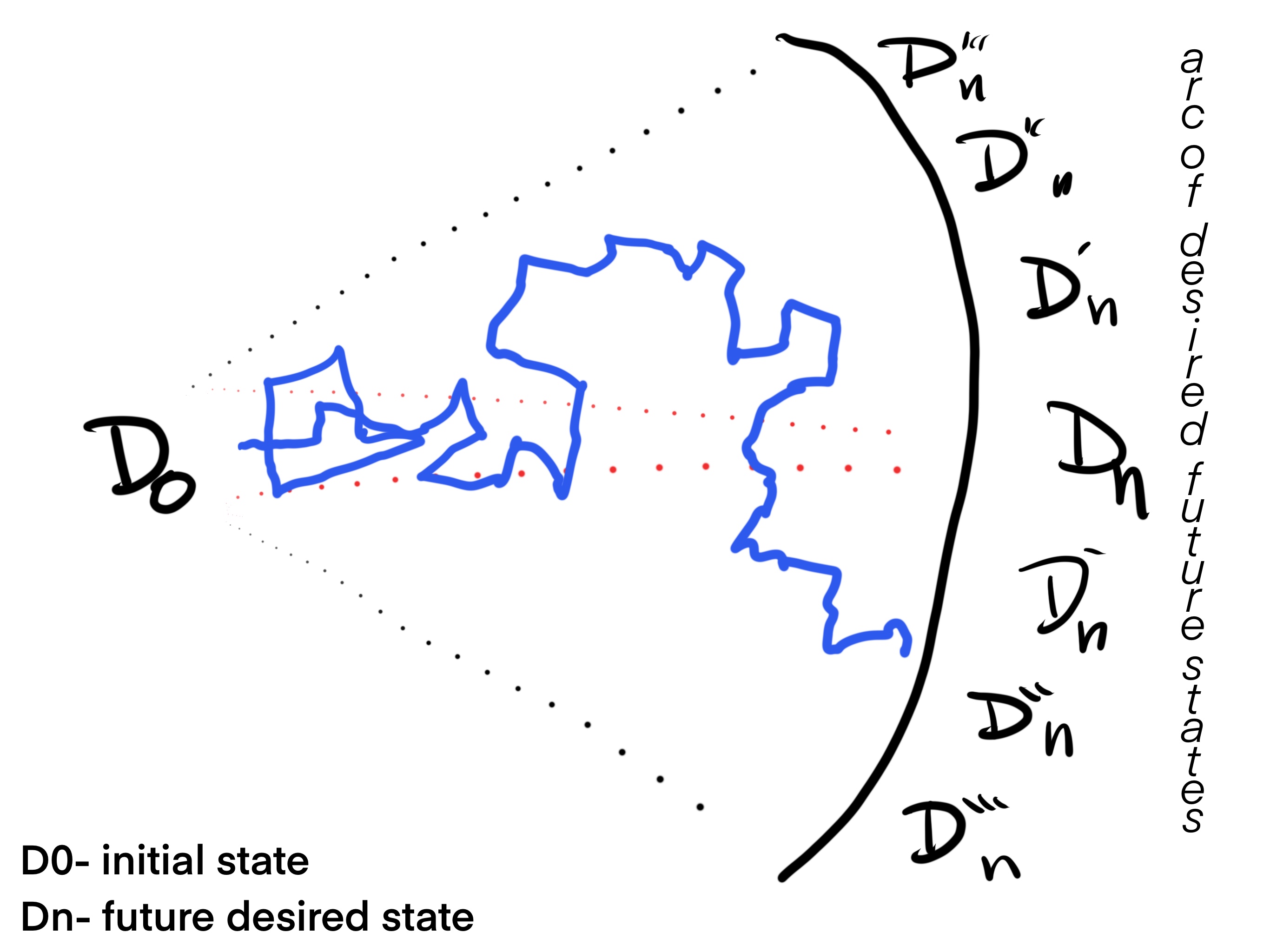

The desired state isn’t a fine, pinpoint location in the future, but is an arc of possible desired future states.

Getting from the present (D0) to the desired future state (Dn) is never a direct path, and the end goal shifts as you move forward and learn new things.

Well-Formed Outcomes

In building a DesiredState, the quality of the description of the outcomes is important to being able to achieve them.

Assertion: quality of life is dependent upon achieving one’s outcomes in life.

Assertion: the quality (value to the person requesting something) of one’s outcomes is in direct proportion to the well-formedness of the outcome.

Outcomes have the following properties. All of these are necessary in order to make the outcome well-formed.

-

Specificity: precisely stated action to be performed and result desired from the action. Specific as to outcome, form, place, time, cost, value, person(s):

-

outcome: what is the desired result from the action? The outcome itself must be stated. A complete picture of the Desired State of the requestor is most useful.

-

form: what form will the result be needed in?

-

place: where will the action be performed and where will the result be delivered?

-

time: when is the result needed and how much time can the action take?

-

cost: what is the budget for carrying out the action and the cost of materials for the result?

-

value: how will the person performing the commitment be compensated and how will the requestor be using the result in future work?

-

person: who is making the request, the commitment response, carrying out the action, delivering the result, receiving the result, and using the result?

-

-

Obtainability: the result must be able to be achieved by the person(s) within the specifications made.

-

Positive: the commitment is for what is wanted, not what is not wanted. There are no statements of the form “Don’t do …” or “I don’t want…”. A positive outcome is easier and richer to specify than the list of things it isn’t supposed to be.

-

Appropriate chunk size: the result requested can be negotiated in a single setting. The requestor must be able to use the result delivered

-

Ecological: the outcome is not harmful to any of those involved, and furthers the goals and needs of the requestor.

Three Golden Questions

The three golden questions are:

- What Do You Want?

- What Will That Get For You?

- How Will You Know When You Have It?

They are golden simply because they are the most powerful form of gathering information about something you or your client wants. If you only had these 3 questions, you can still evoke a lot of personal change in yourself or in your client.

Write these down, and keep them in a prominent place where you can see them all the time.

Many times, these questions are best asked from the future rather that the present.

What Do You Want?

Perhaps the most important question one can ever ask, either of others or of one’s self. Understanding what we want is key to getting what we want. The more specific we are, the more likely we are to get it.

The Three Golden Questions and the Rest Of The Questions build upon this basic question.

The intention of this question is to get as complete a picture of the client’s DesiredState as possible. Having the DesiredState specified in SensoryInformation details helps the client to step into the DesiredState and try it on to see if they like it. It also establishes a set of anchors and criteria they can use to remember what they want when they are in the midst of getting it (remember: “When you’re up to your neck in aligators, don’t forget that the mission was to drain the swamp”).

Alternative ways of asking the same question

- What do you need at this point?

- What would you like to have instead?

- When you don’t have X , what will you have?

- What is the outcome you want?

- Tell me how you’d like this to all end up.

And asking from the future desired state:

- When you have everything working well, what do you have? (from the future looking back.)

- Imagine you now have what it is you want. Can you tell me what that is?

- Put yourself out in time to when you have what you want. What was that?

- What do you have now, in the future when you have it, that you wanted?

These last set of questions require a sort of sleight of mouth – the way they sound to client is important, because they are not very straight-forward syntax-wise, nor in a way most people talk or think. You may need to gently pace your client before you get to such a question.

What Will That Get For You

This question establishes motive and intent. It is useful to ask this because the reasons for wanting a certain thing are often complex, and before there can be a well-formed Desired State (see also Well Formed Outcomes), we must know the reasons why the client wants what they want.

Sometimes the client doesn’t know why they want something. This is why it is important to couch the question the way it is written. Simply asking “Why do you want that?” leaves things far too open for the client to give any answer. The question, as written, will direct the client to think of outcomes, which is what we want here.

It is also useful to explore this territory for awhile. Ask the question at least three times or until you get a business reason, as opposed to a procedural or technical reason.

Some other ways to ask the question include:

- What will you be able to do when you have that?

- What is even more important than having that?

- What problem does having that solve for you?

How Will You Know When You Have It

This question establishes the metric or measure of achieving the outcome. This is how the client wants to receive the outcome. Press the client on this question to get them to think about business metrics, to go along with the business reasons established in What Will That Get For You.

This question is best asked from the future Desired State:

“When you first had d(n), how did you recognize it?”

Here, d(n) represents the sequence of desired states. The current state is d(0), although most likely the current state is not “desired”. It can be useful to stage the future desired state in order to help the client see that what they want can be achieved in stages, and that what they want now might not be their end goal.

Rest Of The Questions

The rest of the questions further specify the desired state:

- Under what circumstances would you not want it?

- When do you want it by?

- Where do you want it; everywhere, all the time?

- With whom do you want it?

- What will you lose by having it?

- What stops you from having it today?

- What do you already have towards getting it?

- What else do you need in order to get it?

- What is the first step?

A final question is to check the Ecology of what the person wants:

Given all this (backtracking), do you still want it?